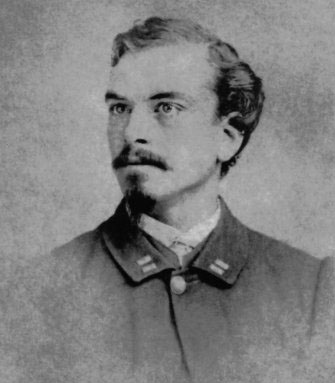

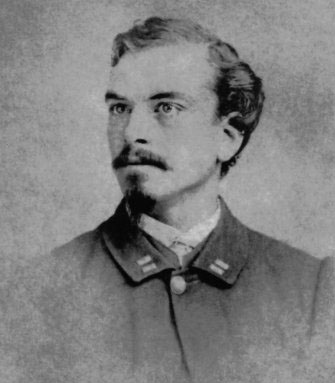

20-year old Captain John Darling Terry,

probably taken late May 1865 or later.

Image from Robert Terry. Used with permission. |

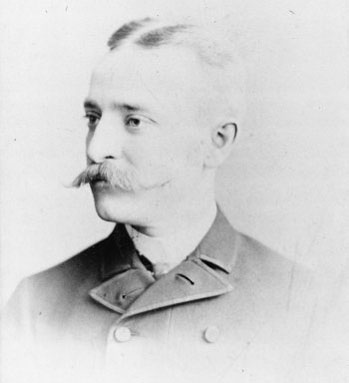

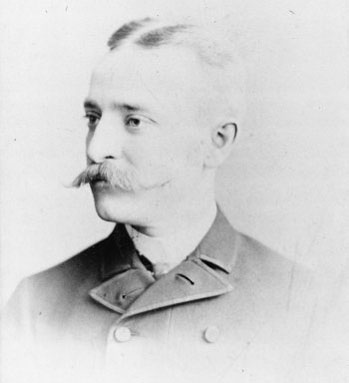

John Darling Terry, later in life,

when he was between 35-40 years old.

Image from Robert Terry. Used with permission.

|

John Darling Terry was born on 3 September 1845, in Montville, Maine. In May 1861, young John Darling Terry left home for Boston, where, on the 23rd, he joined the 1st Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. He was only 15 years old at the time. Terry's service with the 1st Massachhusetts was short-lived. His father notified the U.S. Army that his son was underage; so on 5 July, just two months after he enlisted, Terry was discharged. However, Terry was persistent. On 5 September 1861, just two days after turning 16, Terry joined the 23rd Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry.

Arrival in North Carolina

In March 1862, Terry arrived in North Carolina with the 23rd Massachusetts. Since many of his fellow soldiers came from fishing towns along the New England coast, the soldiers embarked on Union gunboats and attacked Confederate vessels and forts in a naval and amphibious operations around Roanoke Island, near the Virginia border. During one such operation, Terry's gunboat blew up and his clothing caught fire. He jumped into the water to quell the flames, but survived with minor injuries.

On 13 March 1862, Brigadier General John G. Foster led the 23rd Massachusetts and its sister regiments against Confederate forces near the town of New Bern, in northeastern North Carolina. During that battle, Terry, now a sergeant, was shot in the lower left leg, which later had to be amputated below the knee.

In 1882, Terry was interviewed by John S. Pierson for the book Sabre and Bayonet: Stories of Heroism and Military Adventure. In one of the passages, Terry said:

"On the 13th day of March, 1862, the 23rd Regiment Massachusetts Volunteers, landed some 15 miles below Newbern, N.C., my arm still very sore and lame from a contused wound received in the fight at Roanoke Island, some few weeks before. Company E, in which I was a sergeant, was recruited in the old historic town of Plymouth, Mass., strong, healthy, robust young fellows, all of whom were accustomed to the management of boats, and therefore we were detailed to man the boats and disembark the regiment.

I had charge of the vessel's 'cutter,' and worked very hard in order to make the most landings. After the regiment was all ashore we took up line of march by the right flank towards Newbern. It came on to rain very hard and the narrow road was in bad condition. Just before dark we went into bivouac in the woods, on the left of the road, having marched about 13 miles that day, very hungry, cold, wet, sore, and tired. My arms became very painful, and to sleep was entirely out of the question, and to make a fire was contrary to orders.

Daylight, however, broke at last and with a little half cooked coffee and well soaked crackers, we were soon on our way to 'do or die,' and almost before we knew it, were under fire, shooting away for dear life. In going from the road into and up through a little ravine, column of fours, the Col. (John Kurtz) passed us and called to me to go with him. I had been acting as right general guide of the regiment. Soon afterwards the colonel ordered me to go down the rear line and find the lieutenant colonel.

In obeying this order I saw that the regimental line was very ragged; everybody seemed to be all mixed up with one another, and badly scattered from their own companies. I sought out Company E. and found the men brave as young lions, but in bad order and no officer in command, captain wounded. I immediately reported these facts to the colonel, whereupon to my great astonishment and delight, he ordered me to go back and take command of the company. I did so, and succeeded in getting the men well up and together, and they very soon became steady as old veterans.

We had been firing some little time when the lieutenant colonel came to me and asked if I saw a single gun (12 pounder) that the enemy had got out in front of Fort Thompson, this fort contained 12 guns. I answered him that I did. This single gun was doing our ranks great injury.

The lieutenant colonel then asked me if I thought we could charge and take it. We charged, we got the gun, the very last shot from which, before we reached it, got me with seven other comrades, including the lieutenant colonel, killed. My foot was gone, and we were left on the field in very nearly the same spot as where we fell. Our regiment claimed this gun, and (Maj. Gen. Ambrose) Burnside ordered that it should remain with the regiment. Some days after the fight (and my foot had been amputated) Col. Kurtz and Gen. Burnside visited the hospital and the colonel told me that I should have a commission. I got that, and the Congressional Medal of Honor besides."

Terry's actual Medal of Honor citation, issued on 12 October 1867, is terse, but telling:

"In the thickest of the fight, where he lost his leg by a shot, still encouraged the men until carried off the field."

Terry was only 16 years old when he preformed the actions for which he received the Medal of Honor.

Sergeant John Darling Terry's medals.

Image from Robert Terry. Used with permission.

That would have been the end of the war for many, but Terry had different ideas. He was sent to Lexington Army Hospital in New York City, where he was fitted with what was described as a wooden "peg leg." He remained in the hospital for rehabilitation, serving as the sergeant of arms until he was discharged as an "invalid" on 20 March 1863.

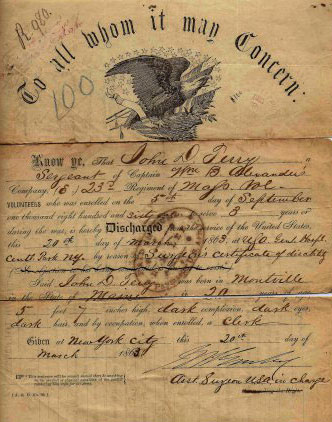

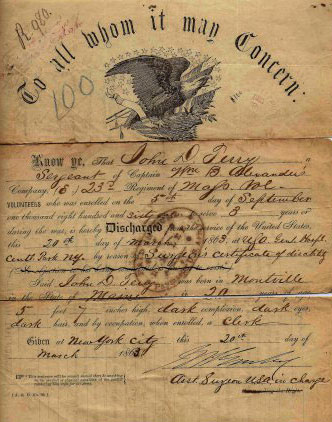

17-year-old Sergeant John Darling Terry's Honorable Discharge.

Image from Robert Terry. Used with permission.

New York Draft Riots

While remaining in New York, Terry attempted to re-enter "active service." In July 1863, the notorious New York draft riots broke out. Terry, now classified as an "invalid" by the Army, volunteered for service with the outnumbered military forces in New York City, where he was ordered by Major General Harvey Brown "to deliver the muskets and ammunition to the Custom House and Post Office authorities for their defense," Terry wrote in a letter.

He continued:

"I was assigned to command a body of convalescent Soldiers and ordered on guard duty in Gramercy Park by order of Gen. Brown, where, on the corner of 21st Street and Third Avenue, I was struck a severe blow over the left eye with a club by a rioter and was badly hurt. I was mentioned in orders issued by Gen. John A. Wool, for the 'Very signal service rendered.'"

It was on day three of the riots, while reinforcements were arriving from the Battle of Gettysburg, that Terry received word of his appointment as a lieutenant in the 1st North Carolina Colored Volunteers. Lieutenant Terry soon headed back south to New Berne to join his new regiment.

Brigadier General Edward A. Wild did the honors of promoting Terry to 1st lieutenant in the 1st North Carolina Colored Volunteers, which was later renamed the 35th U.S. Colored Troops on 8 February 1864. General Wild also was an amputee, having lost his left arm at the Battle of South Mountain in Maryland.

Battle of Olustee

During the Battle of Olustee, 18-year-old 1st Lieutenant Terry was in the thick of the intense fighting, as the 35th U.S.C.T. and the 54th Massachusetts held off the Confederate advance at the end of the day. And once again, a bullet struck his leg. Fortunately, the leg that was hit was his peg leg.

On 2 March 1864, the Connecticut Hartford Evening Press reported the engagement and Terry's ordeal:

"A lieutenant of the same regiment, who had lost a leg in an engagement in North Carolina, and who had supplied in its place with an artificial member consisting of a stout oaken peg, was present at this fight, and, a rebel sharpshooter put a bullet through his trousers leg and his wooden peg. He felt the blow but escaped the twinge of pain that generally accompanies the passage of a pellet through genuine flesh and muscle, and enjoying a keen sense of the ludicrous, he forgot the battle and its dangers, and gave way to the heartiest and most explosive laughter.

He pushed along the line and approached the colonel, to whom, after a severe effort, he was able to communicate the cause of his mirth. Almost convulsed with laughter, he exclaimed, 'colonel! By George! The dammed rebels have shot me through the wooden leg! Ha! Ha! Devilish good joke on the fellows!' and he hobbled back to his position on the line, and chuckled to himself immensely over the sell [sic]."

As darkness fell, the 35th U.S.C.T., along with the survivors from the 54th Massachusetts, disengaged from battle and began the retreat to Jacksonville. In the months that followed, Terry was fitted with two new prosthetics in order to remain in the active service.

On 23 May 1865, Terry accepted a promotion to captain from Brigadier General Rufus Saxton, and was posted as a company commander in the 104th U.S.C.T., effective 16 June. However, on 19 September 1865, the Army withdrew Terry's promotion to captain, citing his disability, and that a captain of a company is expected to march with his command and perform duty on foot with his men.

Post-War

On 23 September 1865, Terry was assigned to Saxton's staff at the Freedmen's Bureau in Charleston, South Carolina. Creation of the Freedman's Bureau was initiated by Lincoln in March 1865, with the purpose of assisting freed slaves. The bureau was under the Department of War and played a major role in post-Civil War Reconstruction until it was disbanded in 1872.

In October 1865, Terry wrote a letter to a family friend, former New York State Senator Preston King, asking that he look into restoring Terry's rank to captain. Major General John G. Foster, who heard the case, denied the senator's petition. King could not reply because he died shortly after receiving Foster's letter.

On 25 November 1865, Terry submitted a letter of resignation, saying he did not wish to serve as a 1st lieutenant after having served as a captain. On 16 December 1865, Terry had second thoughts about leaving the Army and withdrew his letter of resignation. However, Terry was given a brevet promotion to captain on 21 February 1866. A brevet rank comes without the additional pay of the higher rank and exercise of authority is limited. The practice was common during the Civil War.

On 23 January 1866, Terry was transferred to Headquarters, Department of the South, in Charleston, under command of Major General Daniel Sickles, who was still serving within the Freedman's Bureau.

Terry was mustered out of the service on 6 June 1866, with the rank of 1st lieutenant. On 22 June 1867, the Army rewarded Terry by breveting him as major, but his official rank remained 1st lieutenant.

After the war, Terry had a 50-year career at the Customs House in New York City as a deputy collector in the audit department, and he also served as a clerk.

A month after his last discharge (6 June 1866) from the military, Terry married Emma Celia Brown. The services were held at the Rose Hill Methodist Church, 221 East 27th Street, in Manhattan, New York City. Their wedding was officiated by Emma's grandfather, the Reverend Amos Brown. A letter from John's files reads, Reverend Brown "traveled a great distance to be there,"

John Darling and Emma had ten children between 1867 and 1893. Their first son Alexander Haddon was born in 1876. George, their second son, died at an early age and is not listed on the 1880 census. Another son died prior to 1919. A 1919 letter written by another son, Charles Graham, states, "I have 2 brothers and 5 sisters."

John Darling Terry died on 4 March 1919, and is buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in Bronx, New York; Plot: Section 141, Butternut Plot, Lot 14454.

Army Reopens Case

The final chapter of John Terry's story was not completed until nearly 150 years later.

Robert Haddon Terry, John Darling's great-grandson and Alexander Haddon's grandson, was instrumental in providing critical documents, obtained from the National Archives, which he submitted to the Army Board for Corrections of Military Records (ABCMR). The ABCMR is the highest echelon of Army record reviewers. Robert Terry, and other family members, asked the U.S. Army to restore John Terry's rank as captain. In 2013, the ABCMR heard Terry's case. Based on the evidence Bob Terry obtained from the National Archives and elsewhere, the ABCMR ruled in favor of John Darling Terry.

Conrad V. Meyer, ABCMR director, stated:

"Our board has substantial authority and equity and we made the decision that Terry did in fact prove he could serve and lead from the front as a captain, even with the peg leg. Our board felt revocation of his promotion was unjust.

Therefore the board determined that the evidence presented was sufficient to warrant relief and recommended all Army records be corrected by reinstating his permanent rank to captain."

Donald Terry MacLeod Jr., the great, great-grandson of John Terry and also Bob Terry's cousin, has a special interest in his ancestor. MacLeod said his grandmother shared memories with him about John Terry, since she had conversations with him. She was 18 years old when he died.

"My grandmother told me that when they were children he would sit on the porch of their home in Westchester County, N.Y., and take off the wooden prosthesis and show it to them. He would also apparently bang it on the front steps and make them laugh. He supposedly joked that the South had bad aim because when they shot him in the leg the second time they hit the wooden leg."

MacLeod also shared his thoughts on America's evolving attitudes toward race.

"We do feel strongly that his rank of captain was withdrawn due to the change in attitude after Lincoln's death about the officers who were close to the former slaves and working for their good, masked of course by the premise that he couldn't function as a captain with his disability. This is a larger story that is only exemplified by what happened to John D."

Bob Terry shared his thoughts as well, in a letter to the ABCMR.

"In a twist of irony, officers who became amputees such as Generals Wild and Sickles were allowed to remain in service, but enlisted personnel were not. Additionally, Major General Foster obfuscated the issue because he not did attempt to revoke my great-grandfather's commission, but decided simply to demote him from captain back to first lieutenant on the basis that my great-grandfather could not possibly perform the duties of a captain with only one leg.

Extensive records in the National Archives provide clear evidence that my great-grandfather's commission was not fraudulent, that he was already serving honorably as a permanent captain at the time of his demotion, and that he performed admirably as a brevetted major after his demotion. Documentation also shows there was no attempt to hide his disability at the time of his permanent promotion to captain."

During a U.S. Army interview with Bob Terry, he echoed his cousin's thoughts on race as a factor, although Terry himself was not an African-American:

"The idea of correcting the record was his family carrying on a fight that we found he waged up until his death in 1919 to gain justice. The injustice was because John Darling associated with officers like Major (Martin) Delaney, the highest ranking black officer in the war and John's commander of the 104th U.S. Colored Troops; Major Generals (David) Hunter and Wild, who recruited former slaves in South Carolina and North Carolina respectively for the Union Army; Saxton and Sickles, the latter who on Grant's recommendation replaced Saxton after President Johnson fired him for refusing to take back land grants awarded to freed slaves.

My great grandfather and all these officers suffered greatly for the stands they took. But they stood for what was right and fought the war after the war in spite of having to sacrifice rank, position, and peace."

Bob Terry said, as a result of his research, he feels for combat veterans today who are struggling from losses of limbs, other physical injuries, and mental wounds suffered years after.

"Terry lost his limb because he was left on the battlefield for five days and gangrene set in. At the time, there was no ambulatory service and medical care that was provided was appalling by today's standards.

Also, there was a stigma associated with being an invalid. But Terry refused to be labeled as such. He was offered positions in the artillery, home guard and even in the newly formed Invalid Corps. But he turned them all down, wanting instead to go back into the field where he would have to move about on his feet.

I hope Terry's story will be an inspiration for vets who were injured and are struggling today."

Bob Terry and Donald MacLeod welcome inquires and conversation about John Terry. They have a lot more information about John Terry and events surrounding his service and plan to eventually put it all in a book. You can contact Robert Terry at rhterry@windstream.net.

U.S. Army's John Darling Terry Medal of Honor Citation page

John Darling Terry grave site

Wilipedia page on BGen Edward Wild

Information and images provided by Robert Terry and the page on John Darling Terry from the U.S. Army Web site.

Battle of Olustee home page

http://battleofolustee.org/